Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Throughout history, capital and labor have been interdependent forces driving economic growth. Capital relies on labor to generate returns on investment, while labor depends on capital for wages. Despite historical fluctuations in their balance of power, classical economics suggests a theoretical long-term equilibrium where both parties benefit—capital sees growing returns, and labor enjoys rising wages. But is this equilibrium sustainable in the face of rapid technological advancements?

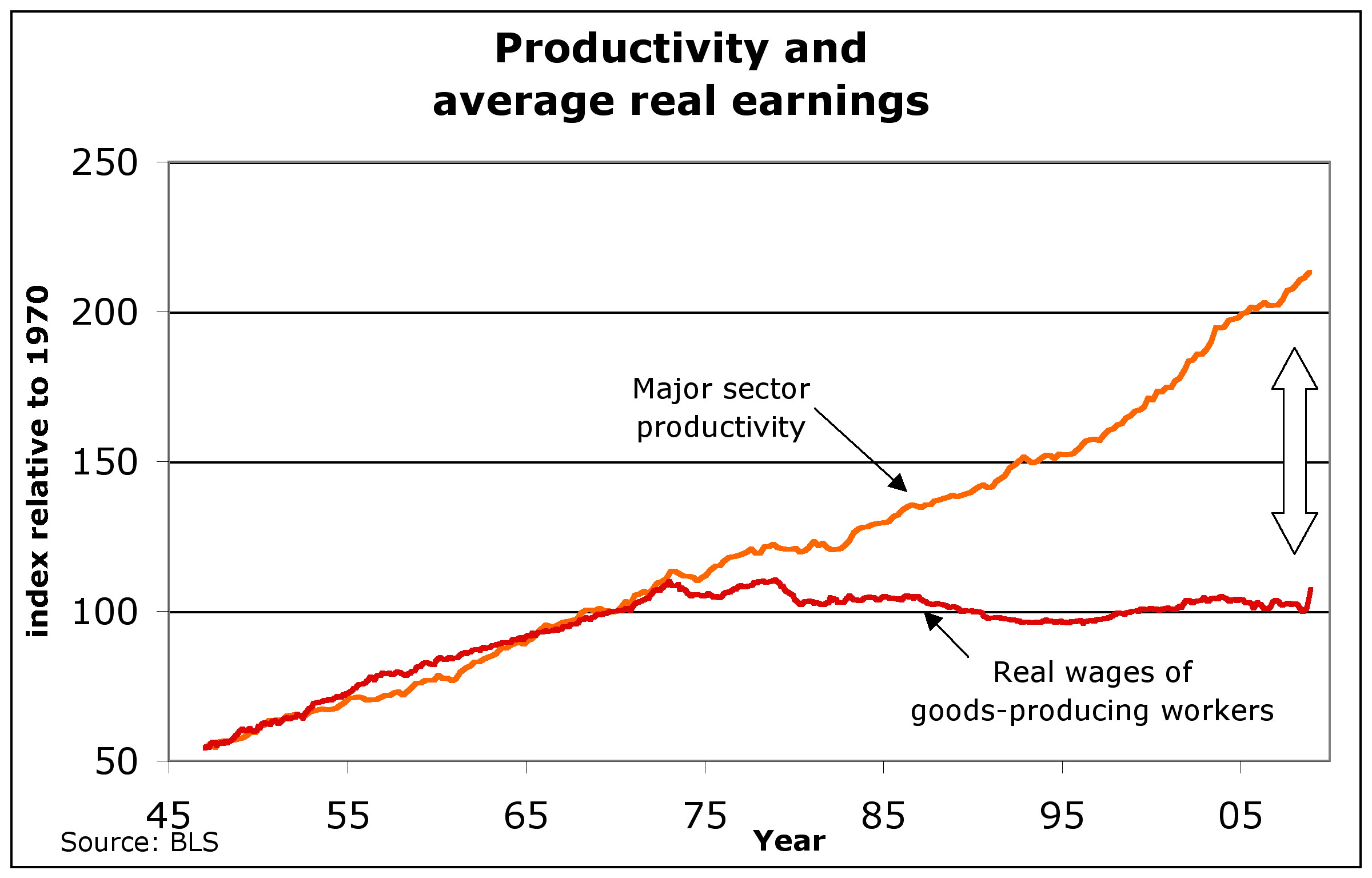

The post-World War II era, particularly from the late 1940s to the early 1970s, exemplifies the mutual benefit of capital and labor. This period saw unprecedented economic growth and a significant rise in the standard of living for the baby boomer generation in North America. However, starting in the 1970s, the balance of power shifted towards capital. This shift was marked by productivity gains increasingly benefiting returns on investment while wages stagnated. As a result, the once-synchronized growth of productivity and wages decoupled, favoring capital over labor and increasing income inequality and social stratification.

This was a substantial quantitative change with proportionally substantial quantitative social implications. Today, we are approaching a qualitatively different watershed moment that will fundamentally shift the balance of power and have profound social and political implications.

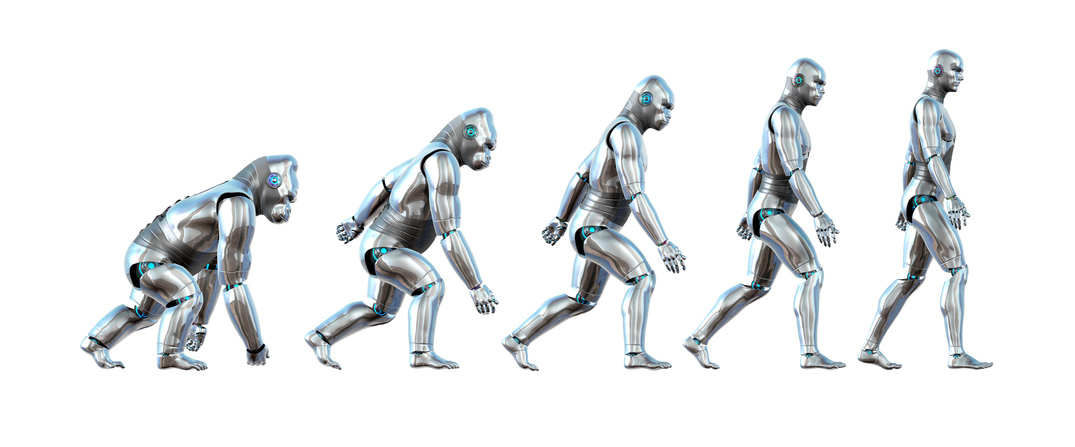

For the first time in history, technological advancements like AI and robotics enable capital to create labor rather than hire it. This shift disrupts the traditional labor-capital relationship, leading to ‘technological unemployment,’ where machines and AI replace human labor across various industries. The longstanding relationship of mutual co-dependence between capital and labor will be profoundly altered, and the equilibrium taught by classical economics will no longer hold, even in theory. The incentive for paying wages diminishes as technologies like AI and robotics increase productivity while reducing costs. It’s like having workers who produce more and more while getting paid less and less. The best part for capital is the ability to create and multiply its own ‘labor’ force or cut it when needed, increasingly faster and cheaper. Humans are not required.

Some argue we have heard similar Luddite concerns before, and historically, technological advances have worked out for the better. However, today’s technological unemployment fundamentally differs from past labor disruptions, such as those during the Industrial Revolution. In the past, displaced workers transitioned from one type of manual job to another, as capital still needed human labor to operate machines, oversee production, and manage resources. Today, machines can autonomously perform these tasks. Production is monitored by sensors, and resource allocation and management are handled by AI, reducing the need for human labor to the point of potential obsolescence.

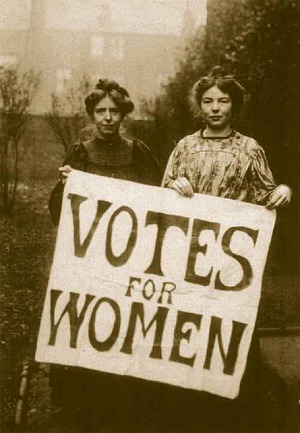

The speed and depth of change we are experiencing today, combined with an accelerating pace, means we will witness much more happen in a much shorter timeframe than during the Industrial Revolution. This is not simply about replacing some manual jobs with others; it’s about making most human jobs obsolete across all industrial levels—from cashiers and production-line workers to accountants, brokers, lawyers, insurance and real estate agents, consultants, doctors, and even CEOs. Such a fundamental change, occurring over a few decades, will have revolutionary political and social implications, similar to how the Industrial Revolution spawned various social movements, uprisings, and political revolutions.

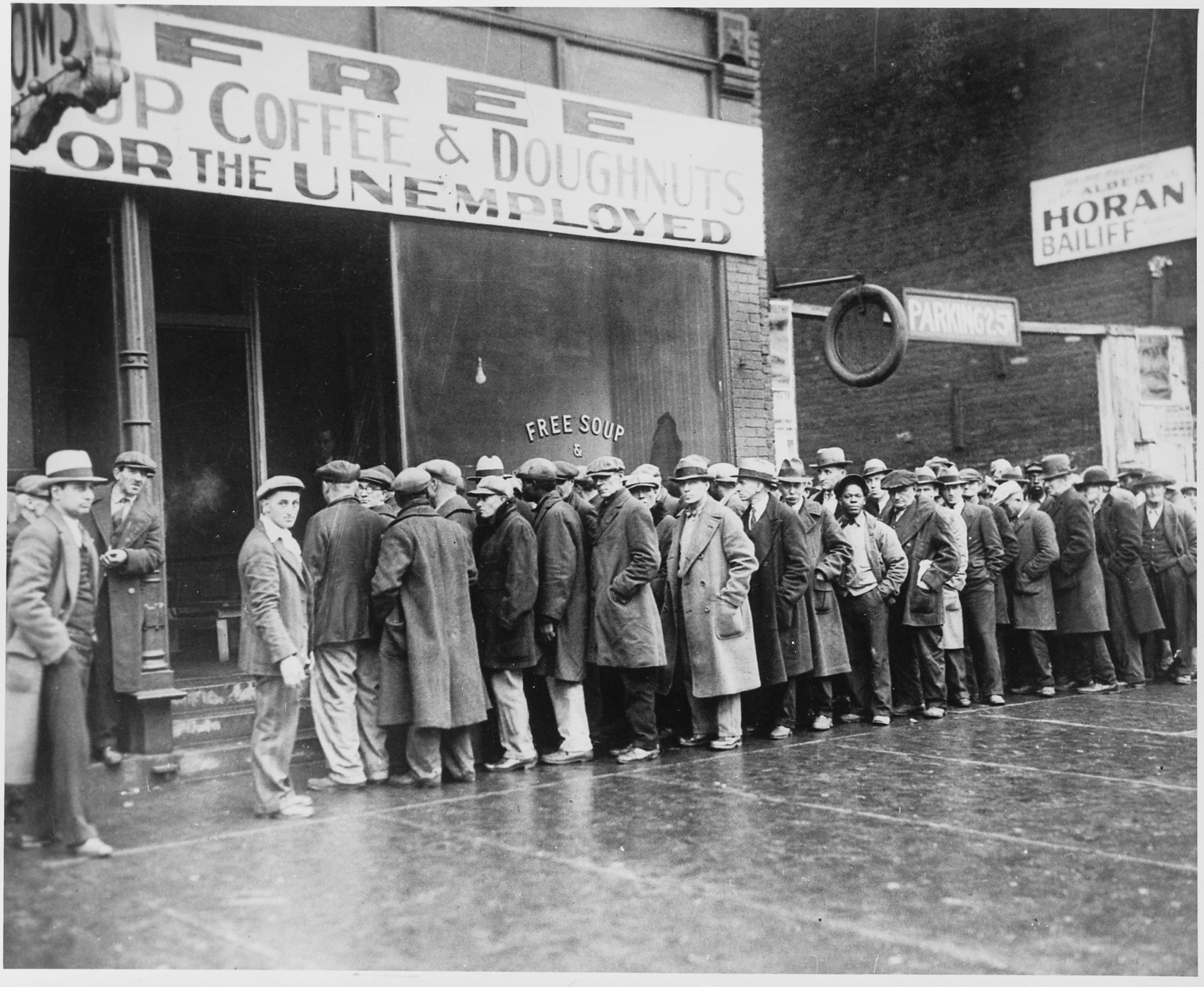

Historian Yuval Harari predicts that the AI revolution will give rise to a ‘useless class,’ much like the Industrial Revolution created the working class. This new class will consist of individuals who are not merely unemployed but unemployable, posing significant social and political challenges. In the past, capital had incentives to preserve labor, as it could not operate without it. While exploitation was common, outright elimination of workers was not economically viable. However, with the advent of machine labor, human workers become obsolete, removing economic incentives to treat them humanely. This could lead to severe consequences, particularly if displaced workers resort to political organization, sabotage, or destruction of property, as historically seen during periods of mass unemployment.

Historically, soldiers were required to suppress dissent and enforce order, and their loyalty was secured through payment. If soldiers went unpaid, regimes often fell. Soldiers, like workers, are another form of human labor. Soon, advanced AI and robotics could replace human soldiers, allowing rich dictators and capitalists to maintain control without human intervention. If one can create machine workers, one can also create machine soldiers, further consolidating power in the hands of those who control the technology.

There are 5 million truck, taxi, and other drivers, plus 3.5 million cashiers in the United States alone. These jobs could disappear within the next 5 years. Eventually, most jobs that exist today may become obsolete. Retraining the unemployed is unlikely to be effective, as we cannot predict the jobs of the future. Even if we could, by the time retraining is complete, those jobs would likely be taken by robots and AI, which are cheaper and faster to train.

The impending wave of technological unemployment could lead to two vastly different outcomes: a ‘useless class’ or, for the first time in history, a ‘free class,’ liberated from the necessity of work and able to pursue creative and leisurely activities. The path we take will depend largely on the actions of major corporations and their willingness to adapt to or resist these changes.

The future of labor and capital is at a critical juncture. The decisions made by corporations and policymakers today will determine whether we face a dystopian future of mass unemployment or a new era of unprecedented freedom and creativity.

Will capital fight to preserve the status quo, or will it embrace the potential of a world where humans are liberated from traditional labor?

Our choices will shape the social, political, and economic landscape for generations to come.

Related Articles

-

- Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren by John M. Keynes

- Marshall Brain on Singularity 1on1: We’re approaching humanity’s make or break period

- Venture Capitalist Albert Wenger on Basic Income and World After Capital

- The Economic Singularity

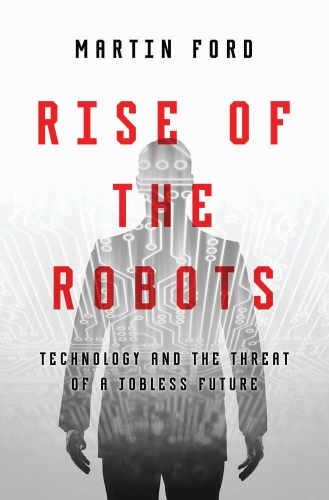

- Martin Ford on Singularity 1on1: Technological Unemployment is an Issue We Need To Discuss

Prof.

Prof.  Many people who think about the future believe that robots and artificial intelligence will take most of our jobs, while many other futurists believe the advances in technology will transform work and create a net increase in jobs. Neither of the aforementioned camps can agree on a set timeline for any of this so we end up with the conclusion that at some point in the future, perhaps starting today or perhaps decades away, we may or may not see an extreme spike in unemployment due to advancements in technology and automation. Furthermore, we may or may not be able to find gainful employment for these people at some point in the remainder of their lifetimes. The solutions to these extreme positions range from a

Many people who think about the future believe that robots and artificial intelligence will take most of our jobs, while many other futurists believe the advances in technology will transform work and create a net increase in jobs. Neither of the aforementioned camps can agree on a set timeline for any of this so we end up with the conclusion that at some point in the future, perhaps starting today or perhaps decades away, we may or may not see an extreme spike in unemployment due to advancements in technology and automation. Furthermore, we may or may not be able to find gainful employment for these people at some point in the remainder of their lifetimes. The solutions to these extreme positions range from a

Steve Morris studied Physics at the University of Oxford and spent ten years working for the UK Atomic Energy Authority. He now runs tech review site

Steve Morris studied Physics at the University of Oxford and spent ten years working for the UK Atomic Energy Authority. He now runs tech review site  At Borg LaborGroup ServisesProducts (BLS) – the largest and leading ‘machine employment agency’ – times are getting giddy and sweet due to the recent $15 per hour minimum wage hike for low-skilled human beings. For technology everywhere it is Christmas, New Years and Happy Birthday all rolled into one. The long, hard slog of machines trying to become stronger, faster, more accurate, more adaptable and continuously and perpetually less expensive, in order to compete, has been made far more comfortable.

At Borg LaborGroup ServisesProducts (BLS) – the largest and leading ‘machine employment agency’ – times are getting giddy and sweet due to the recent $15 per hour minimum wage hike for low-skilled human beings. For technology everywhere it is Christmas, New Years and Happy Birthday all rolled into one. The long, hard slog of machines trying to become stronger, faster, more accurate, more adaptable and continuously and perpetually less expensive, in order to compete, has been made far more comfortable.

About the Author:

About the Author:

Marshall Brain is best known as the founder of

Marshall Brain is best known as the founder of

Martin Ford is the founder of a Silicon Valley-based software development firm and the author of two books: The New York Times Bestselling

Martin Ford is the founder of a Silicon Valley-based software development firm and the author of two books: The New York Times Bestselling