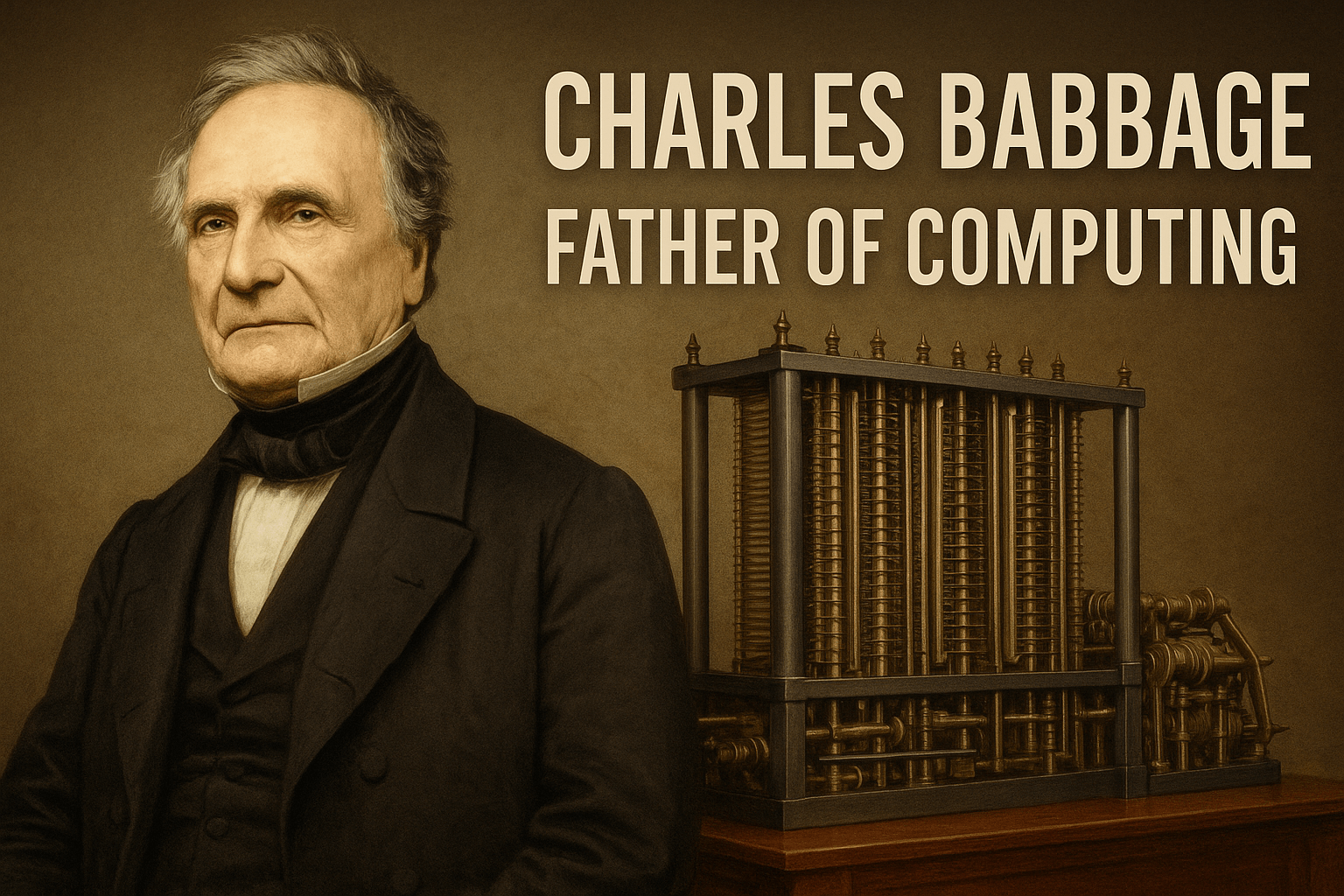

Charles Babbage: The Forgotten Father of Computing and His Relevance to AI

Socrates / Profiles

Posted on: June 17, 2025 / Last Modified: June 18, 2025

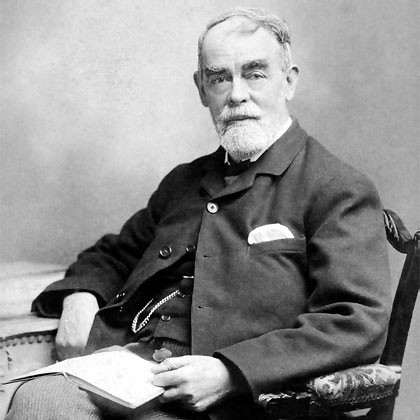

When people think of computing pioneers, names like Alan Turing, John von Neumann, or even Steve Jobs come to mind. But if we zoom out and peer into the deep roots of technological evolution, one name stands as the unacknowledged giant whose ideas still echo through every processor, algorithm, and AI model we create today: Charles Babbage.

When people think of computing pioneers, names like Alan Turing, John von Neumann, or even Steve Jobs come to mind. But if we zoom out and peer into the deep roots of technological evolution, one name stands as the unacknowledged giant whose ideas still echo through every processor, algorithm, and AI model we create today: Charles Babbage.

Born in 1791 in Devonshire, England, Charles Babbage was a mathematician, philosopher, inventor, and—arguably—the father of computing. Long before the first transistor, before silicon chips, before binary code as we know it, Charles Babbage envisioned and partially designed what we would now recognize as the first general-purpose computer: the Analytical Engine.

From Human Computers to Mechanical Precision

In Charles Babbage’s time, “computers” were not machines but people—humans who performed tedious, error-prone calculations for navigation, astronomy, engineering, and finance. Charles Babbage found this profoundly inefficient and deeply flawed. His mission was radical: to mechanize computation, eliminate human error, and automate the production of accurate mathematical tables.

His first significant project was the Difference Engine, a mechanical calculator capable of tabulating polynomial functions using the method of finite differences—essentially avoiding the need for multiplication and division. With roughly 25,000 parts and weighing over 15 tons, the Difference Engine was a monumental undertaking, comprising gears, levers, and precision engineering. But despite securing significant funding, the project was never completed during his lifetime.

The Analytical Engine: A Vision Centuries Ahead

Undeterred by the setbacks of the Difference Engine, Charles Babbage conceived an even more ambitious machine: the Analytical Engine. Unlike its predecessor, this was no mere calculator but an actual computational engine, incorporating core features that would later define modern computing: sequential control, conditional branching, looping, memory storage (the “store”), and a central processing unit (the “mill”).

Charles Babbage was inspired by Joseph Jacquard’s programmable loom, which used punch cards to input both data and instructions—an early precursor to modern programming.

The Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves. Ada Lovelace

Speaking of Ada Lovelace—often regarded as the first computer programmer—she not only understood Charles Babbage’s grand vision but also wrote the first documented algorithm intended for machine execution: a program for calculating Bernoulli numbers. Had the Analytical Engine ever been fully constructed, Ada’s code would have run on it.

Proof of Concept: A Machine That Could Have Worked

Between 1846 and 1849, Charles Babbage refined his designs further, producing plans for a second Difference Engine—this time more efficient, requiring only about 8,000 parts. Although Charles Babbage himself never built it, the Science Museum in London successfully constructed a fully functioning version in 1991, demonstrating that his 19th-century vision was mechanically sound and entirely feasible.

If unwarned by my example, any man shall undertake and shall succeed in really constructing an engine … I have no fear of leaving my reputation in his charge. Charles Babbage

The Paradox: Simplicity vs. Complexity

Here lies one of the great ironies of technological progress—the very machines intended to simplify our lives often make them more complex. Charles Babbage sought to eliminate errors, streamline calculations, and automate tedious work. Today, our computing machines are billions of times more powerful. Yet, we find ourselves overwhelmed by data, paralyzed by choice, and increasingly challenged by the ethical dilemmas of AI and automation.

We have built machines that calculate faster than any human, generate language, compose art, diagnose illness, and even write code—all direct descendants of Charles Babbage’s original vision. But in our rush toward exponential progress, we must ask: Are we wiser for it? Do we harness this computational power to promote human flourishing, or are we being swept along by the very complexity we have created?

The Legacy of Charles Babbage in the Age of AI

As someone who spends his days exploring the intersection of humanity, technology, and the future, I often say: technology is not destiny; it is a magnifying mirror. It amplifies our values, our ethics, and our choices. Charles Babbage’s work is not just historical curiosity — it’s a reminder that every technological leap contains within it both promise and peril.

Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine was, in essence, a prototype for Artificial General Intelligence (AGI): a machine capable, at least in theory, of performing any computation that can be conceived. Today, as we stand on the cusp of potentially realizing AGI, revisiting Charles Babbage’s journey is more relevant than ever. His work forces us to confront not just how we build machines, but why we build them.

Watch and Learn More

To dive deeper into Charles Babbage’s life and work, you can watch these insightful videos:

Charles Babbage: Father of the Computer

Babbage’s Difference Engine No. 2

The future is never entirely new. Every breakthrough stands on the shoulders of those who dared to imagine. Charles Babbage imagined a future we are only now beginning to fully realize. The question remains: will we build machines that serve us, or ones we serve?