Facebook’s Quiet Confession: The Social Network Was a Lie

Socrates / Op Ed

Posted on: January 26, 2026 / Last Modified: January 26, 2026

In an antitrust case brought by the Federal Trade Commission, Meta filed a brief in August 2025 containing an admission that should have been headline news.

In an antitrust case brought by the Federal Trade Commission, Meta filed a brief in August 2025 containing an admission that should have been headline news.

According to Meta’s own data, only 7% of time spent on Instagram and 17% of time spent on Facebook involves “socializing” with friends and family. The overwhelming majority of activity is something else entirely: watching algorithmically selected, short-form videos from accounts you don’t know, chosen not by your human relationships but by AI systems optimized for engagement.

This was not framed as a philosophical reckoning. It was a legal argument. But it quietly confirms something many of us have argued for years:

The “social network” was never truly social. That is no longer even debatable.

When a Category Collapses

If the above single-digit percentages of Instagram use and mid-teens percentages of Facebook use qualify as “social,” then the term itself has lost coherence. At that point, “social network” isn’t just misleading. It’s an oxymoron.

What Meta now openly describes is not a network of people, but a content distribution system. A personalized broadcast channel. A recommendation engine that treats human relationships as a rounding error.

This shift did not happen by accident. It is the logical endpoint of an advertising-driven model that discovered that connection does not scale as well as compulsion.

Friends are finite. Attention is not.

From Connection to Consumption

Meta’s strategy has been clear for years: make Facebook more like Instagram, and make Instagram more like TikTok. Endless feeds. Ever-changing timelines. Nothing stable, nothing permanent, nothing finished, nothing to suggest you can leave.

What once felt like a digital commons now feels like a casino floor: designed for frictionless immersion, not reflection. Pull to refresh. Spin again. Maybe this time you’ll hit dopamine.

I feel this shift personally. Facebook increasingly feels like work. Not because it’s difficult, but because it demands a kind of cognitive submission I’m less and less willing to give. Perhaps that’s age. [I turn 50 this year]. Or perhaps it’s clarity.

Six or seven years ago, saying “I deleted Instagram” sounded like an eccentric boast. In 2026, it can sound like liberation. Not because it signals virtue, but because it signals something far rarer: the agency to choose, and the ability to escape.

The Price of “Free”

None of this is mysterious. The business model explains everything.

Advertising-driven platforms do not sell community. They sell predictability. To advertisers. To political campaigns. To anyone willing to pay for influence over human behavior.

“Engagement” became the sacred metric not because it made us wiser, kinder, or more connected but because it made us measurable and modifiable.

Outrage, it turns out, is extremely engaging. So is fear. So is envy. So is tribalism. Algorithms did not invent these traits; they amplified them, because amplification is what the model rewards.

This is not a bug. It is the system functioning as designed.

What Happens When You Step Away

Here’s the part that rarely makes it into the hype cycles: when people step away from constant connectivity, their lives often improve.

Controlled studies have shown that blocking mobile internet, even temporarily, can improve mental health, focus, and subjective well-being. People spend more time exercising, socializing face-to-face, and going outdoors. Not because they’re instructed to, but because the default changes.

Schools that restrict phones see measurable gains in learning outcomes. Denmark, once an early evangelist of digital education, has resorted to locking phones during the school day and returned to physical textbooks.

These are not Luddite reactions. They are course corrections.

Attention, Development, and the Unpriced Externality

We should be careful with simplistic claims about cognition and screens. Reality is nuanced. But it is no longer controversial to say that attention environments shape development, especially early on.

Emerging research links high levels of early screen exposure with later differences in brain network development and anxiety-related outcomes. Causality is complex. But the direction of concern is clear enough to justify restraint.

The deeper issue is not screens per se. It is systems designed to maximize time-on-device, regardless of developmental stage, psychological cost, or social consequence.

These costs are real. They’re just not priced into the business model.

The New Status Symbol: Unreachability

Something interesting is happening at the cultural margins.

Phone-free schools. Device-confiscating clubs. Luxury retreats where digital silence is sold at a premium. Being offline is increasingly framed not as deprivation, but as privilege.

Some call it digital privilege: the ability to log off without losing your livelihood, your relevance, or your social life. Not being reachable, it turns out, may be one of the most expensive lifestyle upgrades available.

Even public figures increasingly admit what was once unsayable: that they envy people who can simply delete their profiles and disappear.

The Value of the Unshared Life

Angus Fletcher talks about “hidden victories,” the wins that matter precisely because they are kept private, not shared or optimized for public display or maximum engagement.

I’ve never felt compelled to publish my life. Lately, I feel I’ve shared too much.

There’s a scene in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty where a legendary photographer chooses not to take the picture of a rare snow leopard because the moment is too special to be converted into content. That scene stays with me more each year.

Not everything meaningful should be captured. Some things are diminished by being extracted.

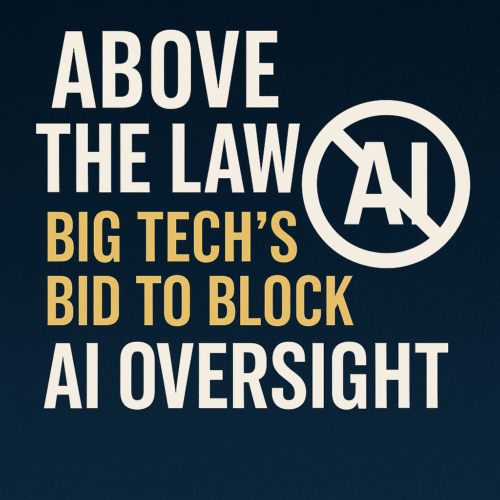

Why Meta’s Admission Matters

Meta’s filing was not a moral apology. It was not a cultural reckoning. It was a strategic statement in a legal battle.

And yet, it matters. Because it confirms the diagnosis.

When it serves them, even Meta is willing to admit that what we call “social media” is not primarily about social connection. The platforms that promised to bring us together have become systems that monetize separation, attention, and behavioral prediction.

Years ago, I called much of this fake: fake friends, fake change, fake connection. Now, quietly, in court documents, the company that built the modern social network is admitting the same thing.

The Question That Remains

The future will not be decided by whether we love or hate technology.

It will be decided by whether we are willing to draw lines.

Whether we treat attention as a public good, not a resource to be strip-mined.

Whether we demand business models that do not depend on addiction.

Whether we build norms – at home, in schools, and at work – that protect depth, presence, and genuine connection.

Whether we remember that the most important parts of life often leave no data trail at all.

Because the next phase is not simply social media with AI.

It is AI systems that have learned to model our biology, map our neurology, and predict our psychology; programmed to hijack attention in the service of goals not of our own.

Meta’s quiet confession makes one thing clear: the problem is no longer hidden.

What remains unresolved is not whether we can see the system clearly, but whether we are willing to say no to it.