How Our Machine Story Shaped Modernity and Why It Can’t Shape the Future

Socrates / Op Ed

Posted on: December 28, 2025 / Last Modified: December 28, 2025

Not everything that endures is optimized.

Our body is a machine.

Our brain is a machine.

Animals are machines.

Soil is a machine.

Our planet is a machine.

Nature itself is a machine.

The machine is everywhere and everything.

This story has become so familiar that it now passes for common sense. We speak of hardwiring beliefs, rewiring habits, optimizing systems, debugging organizations, and scaling solutions. When something fails, we assume a component is broken. When something works, we assume it can be replicated indefinitely.

But what if this is the wrong metaphor?

What if it is the wrong story?

And what if many of our deepest ecological, technological, and cultural crises are not failures of intelligence, but failures of imagination?

Why the Machine Story Worked

The machine story did not arise by accident. It was one of the most powerful ideas humanity ever invented.

Seeing the world as a mechanism allowed us to isolate variables, test hypotheses, and build reliable knowledge. It delivered modern science, industrial productivity, medicine, and computation. It replaced superstition with explanation, fate with intervention.

It didn’t just work.

It worked spectacularly.

In doing so, it became the dominant metaphor of modernity, shaping how we understand science, economics, technology, and progress itself.

But every metaphor, like every model, is a tool — not a truth.

And just as stories do, tools have limits.

The machine story was built for control, prediction, and efficiency. It excels in closed systems with clear inputs and outputs. It struggles, sometimes catastrophically, when applied to open, adaptive, living realities.

Yet we keep applying it anyway.

From Machine to Organism

A machine is assembled.

An organism grows.

A machine is optimized for efficiency.

An organism is optimized for survival, resilience, and adaptation.

A machine has an external purpose imposed upon it.

An organism carries its purpose from within.

When we treat forests as machines, we measure yield.

When we treat them as organisms, we ask whether they can regenerate.

When we treat societies as machines, we engineer control systems.

When we treat them as organisms, we shape the conditions that allow for self-organization and shared meaning.

When we treat humans as machines, we ask how to optimize performance.

When we treat them as organisms, we ask what conditions allow them to flourish.

This difference is not sentimental.

It is practical.

An optimized machine can collapse instantly.

A healthy organism bends, adapts, and survives.

From Machine to Story

Machines are indifferent to outcomes.

Stories determine what outcomes mean — and why they matter.

Machines process inputs.

Stories shape meaning, identity, and action.

Humans do not live inside systems — we live inside narratives. We cooperate, resist, justify, and sacrifice not because a system demands it, but because a story makes it make sense.

The machine story quietly drains the world of meaning. Moral questions are reframed as technical ones. Responsibility becomes diffuse. Harm becomes collateral. Ethics becomes optional.

The danger is not that machines are becoming more human.

The danger is that humans are becoming more mechanical in how they explain the world.

When everything is framed as inevitable system behavior, no one is accountable. When intelligence is reduced to computation, wisdom disappears. When progress is defined solely as efficiency, meaning erodes.

Stories, unlike machines, insist on questions machines cannot answer:

What is this for?

Who benefits?

Who bears the cost?

From Machine to Process

A machine is a thing.

Reality is a happening, a becoming.

The universe is not a static assembly of parts, but an ongoing process.

Life is not an object but an activity. Identity is not a noun but a verb.

The machine metaphor freezes the world.

Process thinking restores motion.

Evolution is not optimization toward perfection; it is continuous adaptation under constraint. Culture is not a finished product; it is a living conversation. Technology is not destiny; it is a set of choices unfolding over time.

When we mistake becoming for being, we treat change as malfunction. We try to fix what is actually transforming.

And in doing so, we often break what we do not understand.

When the Machine Story Turns Dangerous

The problem is not that the machine story is false.

The problem is that it has outlived its usefulness.

Applied without restraint, it:

- Encourages extraction over regeneration

- Treats humans as resources rather than participants

- Frames intelligence as speed rather than judgment

- Promises control where humility is required

A metaphor that once shaped modernity can no longer shape a viable future.

This is especially visible in our relationship with technology. Artificial intelligence, framed through a purely mechanical lens, becomes either a god or a threat but rarely a responsibility.

We ask what it can do before asking what it should do.

We ask how fast it scales before asking what it amplifies.

We ask how to deploy it before asking what kind of world it reinforces.

Every future we imagine is constrained by the metaphors we use to imagine it.

Telling a Different Story

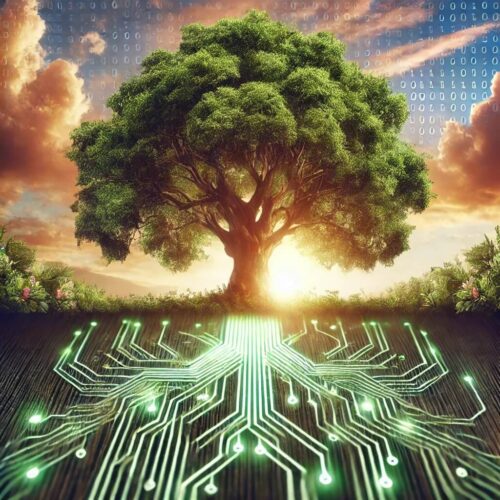

What if instead of machines, we are organisms embedded in ecosystems of meaning?

What if intelligence is not merely computation, but judgment exercised under uncertainty?

What if progress is not acceleration, but learning when to slow down?

What if the world is not something to be optimized, but something that flourishes through care, not control?

These questions are not anti-technology.

They are anti-reductionist.

They ask us to move from domination to stewardship, from control to care, from efficiency to wisdom.

We became powerful by seeing the world as a machine.

We may survive by learning to see it differently.

The question is not whether we can build smarter machines.

It is whether we can tell a wiser story — before the old one breaks down.