If Death Is Natural Then Why Are Some Immortal?

Woody Alen famously quipped that he doesn’t want to accomplish immortality through his work but through not dying. But we are often told that death is natural. Much of the time the statement is left hanging without support as if it is totally obvious. Occasionally, someone will go the extra mile by repeating the (Buddhist?!) mantra that everything and everyone born will die and become food and/or raw material for the next generation – the proverbial great circle of live.

Woody Alen famously quipped that he doesn’t want to accomplish immortality through his work but through not dying. But we are often told that death is natural. Much of the time the statement is left hanging without support as if it is totally obvious. Occasionally, someone will go the extra mile by repeating the (Buddhist?!) mantra that everything and everyone born will die and become food and/or raw material for the next generation – the proverbial great circle of live.

But the above claim is at best incomplete. And, at worse, totally false. First of all it doesn’t acknowledge or explain the great variability of life spans we find out there in the “natural world.” Why, for example, some creatures live many times the average human life? What is it that makes them better, more natural, more suited to or worthy of longer lives than us? Why is it natural for a sea shell or a sponge to live for 400 or 1,500 years respectively, while humans are “naturally” capped at 100 or so?

Secondly, and more importantly, what about the growing list of organisms that have skipped the philosophical debate altogether and have already embraced different versions of biological immortality?! Is that a sign that, having realized they will never achieve immortality through their work, those organisms had no other option but to go for the real thing?!

If death is natural then why do some organisms seem to be immortal?

If you are not familiar with those creatures here is a short list:

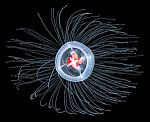

1. The Turritopsis Nutricula aka the Immortal Jellyfish: Technically known as a hydrozoan, it is the only known animal that is capable of reverting completely to its younger self. The jellyfish does this through the cell development process of transdifferentiation. Scientists believe the cycle can repeat indefinitely, rendering it potentially immortal. [The main issue often raised by critics with this process is one of identity – is the offspring considered to be the same specimen or not. Most biologists argue that it isn’t. In fact, bacteria are also said to be biologically immortal, but only at the level of the colony, since the two daughter bacteria resulting from cell division of a parent bacterium can be regarded as unique individuals.]

1. The Turritopsis Nutricula aka the Immortal Jellyfish: Technically known as a hydrozoan, it is the only known animal that is capable of reverting completely to its younger self. The jellyfish does this through the cell development process of transdifferentiation. Scientists believe the cycle can repeat indefinitely, rendering it potentially immortal. [The main issue often raised by critics with this process is one of identity – is the offspring considered to be the same specimen or not. Most biologists argue that it isn’t. In fact, bacteria are also said to be biologically immortal, but only at the level of the colony, since the two daughter bacteria resulting from cell division of a parent bacterium can be regarded as unique individuals.]

2. The Hydra is a genus of small, simple, fresh-water animals that possess radial symmetry. Hydra are predatory animals belonging to the phylum Cnidaria and the class Hydrozoa. They can be found in most unpolluted fresh-water ponds, lakes, and streams in the temperate and tropical regions and can be found by gently sweeping a collecting net through weedy areas. They are multi-cellular organisms which are usually a few millimeters long and are best studied with a microscope. Biologists are especially interested in Hydra due to their regenerative ability; and that they appear not to age or to die of old age.

2. The Hydra is a genus of small, simple, fresh-water animals that possess radial symmetry. Hydra are predatory animals belonging to the phylum Cnidaria and the class Hydrozoa. They can be found in most unpolluted fresh-water ponds, lakes, and streams in the temperate and tropical regions and can be found by gently sweeping a collecting net through weedy areas. They are multi-cellular organisms which are usually a few millimeters long and are best studied with a microscope. Biologists are especially interested in Hydra due to their regenerative ability; and that they appear not to age or to die of old age.

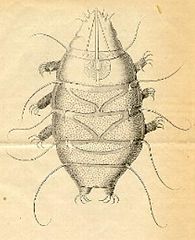

3. Tardigrades (commonly known as waterbears or moss piglets) are small, water-dwelling, segmented animals with eight legs. Tardigrades are notable for being one of the most complex of all known polyextremophiles. (An extremophile is an organism that can thrive in a physically or geochemically extreme condition that would be detrimental to most life on Earth.) For example, tardigrades can withstand temperatures from just above absolute zero to well above the boiling point of water, as well as pressures greater than any found in the deepest ocean trenches, ionizing radiation — at doses hundreds of times higher than would kill a person and have lived through the vacuum of outer space. They can go without food or water for nearly 120 years, drying out to the point where they are 3% or less water, only to rehydrate, forage, and reproduce.

3. Tardigrades (commonly known as waterbears or moss piglets) are small, water-dwelling, segmented animals with eight legs. Tardigrades are notable for being one of the most complex of all known polyextremophiles. (An extremophile is an organism that can thrive in a physically or geochemically extreme condition that would be detrimental to most life on Earth.) For example, tardigrades can withstand temperatures from just above absolute zero to well above the boiling point of water, as well as pressures greater than any found in the deepest ocean trenches, ionizing radiation — at doses hundreds of times higher than would kill a person and have lived through the vacuum of outer space. They can go without food or water for nearly 120 years, drying out to the point where they are 3% or less water, only to rehydrate, forage, and reproduce.

4. Planarian flatworms: Planarian flatworms appear to exhibit an ability to live indefinitely and have an “apparently limitless [telomere] regenerative capacity fueled by a population of highly proliferative adult stem cells.”

4. Planarian flatworms: Planarian flatworms appear to exhibit an ability to live indefinitely and have an “apparently limitless [telomere] regenerative capacity fueled by a population of highly proliferative adult stem cells.”

Planaria can be cut into pieces, and each piece can regenerate into a complete organism. Cells at the location of the wound site proliferate to form a blastema that will differentiate into new tissues and regenerate the missing parts of the piece of the cut planaria. It’s this feature that gave them the famous designation of being “immortal under the edge of a knife.”

Very small pieces of the planarian, estimated to be as little as 1/279th of the organism it is cut from, can regenerate back into a complete organism over the course of a few weeks. New tissues can grow due to pluripotent stem cells that have the ability to create all the various cell types. These adult stem cells are called neoblasts, which comprise around 20% of cells in the adult animal. They are the only proliferating cells in the worm, and they differentiate into progeny that replace older cells. In addition, existing tissue is remodeled to restore symmetry and proportion of the new planaria that forms from a piece of a cut up organism. The organism itself does not have to be completely cut into separate pieces for the regeneration phenomenon to be witnessed. In fact, if the head of a planaria is cut in half down its centre, and each side retained on the organism, its possible for the planaria to regenerate two heads and continue to live.

5. Lobsters: Because they are prized as a delicacy seafood, most people are familiar with those large marine crustaceans – they have long bodies with muscular tails, and live in crevices or burrows on the sea floor. Three of their five pairs of legs have claws, including the first pair, which are usually much larger than the others. What most people don’t know, however, is that older lobsters are more fertile than younger lobsters. Lobsters also keep growing throughout life, don’t show any signs of ageing and have been reported to live 100 or even 200 hundred years before ending on someone’s dinner table.

5. Lobsters: Because they are prized as a delicacy seafood, most people are familiar with those large marine crustaceans – they have long bodies with muscular tails, and live in crevices or burrows on the sea floor. Three of their five pairs of legs have claws, including the first pair, which are usually much larger than the others. What most people don’t know, however, is that older lobsters are more fertile than younger lobsters. Lobsters also keep growing throughout life, don’t show any signs of ageing and have been reported to live 100 or even 200 hundred years before ending on someone’s dinner table.

In addition to the above five examples, there are a few other potential candidates that may have accomplished biological immortality. Some of the best known applicants are the Rougheye Rockfish, the Aldabra Giant Tortoise, the sea anemone and others. And chances are that we will continue to discover other similarly fascinating biologically immortal organisms.

Now, we have to be clear that biological immortality doesn’t mean actual immortality. There is a full spectrum of other causes that can lead to death. [For example, you can be a 200 year old fish or lobster and still get caught and eaten.] It is with this recognition in mind that Dr. Aubrey de Grey is very careful with the language he uses when describing his work – prolonging healthy life-span, defeating ageing etc. De Grey often stresses that he is not working on immortality because, for example, perfectly healthy people can and do get run over and killed by cars every day. So Aubrey insists on being clear that his work focuses on the internal, biological factors, and not the external ones, which are outside of his control. And it is the former that are usually associated with “the natural causes for death.”

But if they are so “natural” then why do some organisms seem to avoid them altogether?! And, more generally:

If death is natural then why are some biologically immortal?

To me the answer is clear – there is no such thing as “natural”! The world is full of diversity and organisms do what they can to adapt in the best way possible to ensure survival. Therefore I see absolutely nothing wrong or unnatural with us using smart technology to achieve biological immortality. There is not such thing as “natural death”. There is only death and a variety of causes that can lead to it. Just like we managed to eliminate death from the plague, we would eventually be able to eliminate death from old age. This may not mean the death of death proper but it will certainly go a long way because it will be the death of “natural death”!

Related articles

- Can a Jellyfish Unlock the Secret of Immortality? (NYTimes)

- Do you want to live forever? (SingularitySymposium.com)

- The Fable of the Dragon-Tyrant [by Nick Bostrom] (SingularityWeblog.com)

- The Methuselah Generation: The Science of Living Forever (SingularityWeblog.com)

- Death to Death! [I Won’t Go Gentle Into That Good Night!] (SingularityWeblog.com)